Tibetet Segítő Társaság Sambhala Tibet Központ

Tibet Support Association Sambhala Tibet Center

székhely / telephely H-Budapest I. Attila út 123..

(00-36) 70 431 9343 (00-36)70 944 0260 (06-1)782 7721

sambhala@tibet.hu www.tibet.hu tibetpress.info

Facebook/Sambhala Tibet Központ Facebook/Tibett Segítő Társaság

MagnetBank/ 16200010-00110240

IBAN/HU94 16200010 00110240 00000000 SWIFT/HBWEHUHB

(1%) adószám/ 18061347-1-41

nyitva tartás/hétköznap 12.00-20.00 hétvégén előadás függő

» Retro» Tibeti művészet» Interjú» Levelek» Tibet Press» Tibet Press English» Dharma Press» Human Rights» Világ» Kína» Magyar» Ujgur» Belső-Mongólia » KőrösiCsoma» Élettér» Határozatok» Nyilatkozatok» tibeti művészet» lapszemle.hu» thetibetpost.com» eastinfo.hu» rangzen.net» ChoegyalTenzin» tibet.net» phayul.com» DalaiLama.com» vilaghelyzete.blogspot.com» Videók» Linkek» TibetiHírek» Szerkesztőség

Hogyan vezetett Jimi Hendrix Bob Dylannel kapcsolatos rögeszméje Woodstockba

2016. március 15./Cuepoint/TibetPress

Jelenleg csak angolul olvasható. Magyarul később.

eredeti cikk

It goes deeper than “All Along the Watchtower”

The two men couldn’t be more different. One is a psychedelic dandy in Swinging London, blasting rock into the future with his frenzied guitar solos; the other is singing country songs and sea shanties in a pink house in West Saugerties. Yet Jimi Hendrix is another Bob Dylan disciple who will eventually follow the master upstate in search of whatever he has found in the Catskill mountains.

For Hendrix, Dylan is the man who’s proved it is possible to be an artist — and a poet — within the circus of popular music. “Dylan really turned me on,” he said in March 1968. “Not the words or his guitar, but as a way to get myself together.” Without Dylan, indeed, he suspects he might never have grown beyond his talent as a guitar phenomenon. “Bob and I once went to see Otis Redding at the Whisky a Go Go in LA,” says filmmaker Donn Pennebaker, director of the Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back. “Otis wanted to get Dylan, and Jimi was the same way. Dylan was the magic thing, and anything that connected with Dylan they would have done at the drop of a hat.” (The Redding show that Dylan saw was on April 8, 1966, with some of the performances included on the 1968 Stax album In Person at the Whisky a Go Go.)

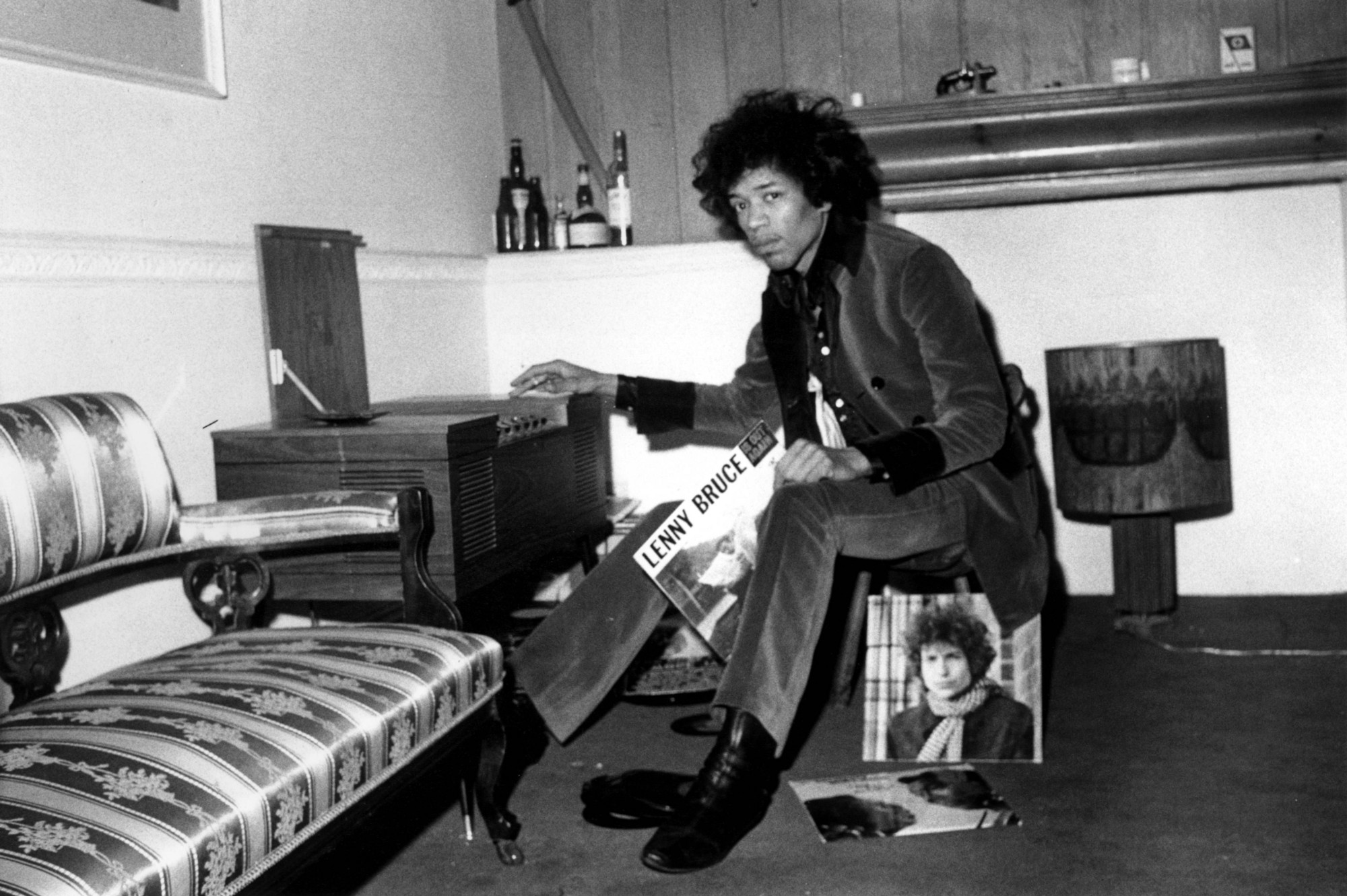

Though Hendrix has only met Dylan once — a fleeting encounter at the Kettle of Fish in the Village — he is obsessed by (and indeed covers) songs such as “Like a Rolling Stone.” He even styles his hair to make it look like Dylan’s wild bird’s nest of 1966. When publicist Michael Goldstein gives him the Dylan manager Albert Grossman-authorized demos from Dylan’s basement sessions, Hendrix records at least one of the songs, “Tears of Rage,” during an early London session for Electric Ladyland. “He came in with these Dylan tapes,” said the late Andy Johns, an engineer at Olympic Studios. “We all heard them for the first time in the studio.”

Hendrix has also just obtained a copy of the newly released John Wesley Harding and decides to cover “All Along the Watchtower.” From its beginnings at Olympic, the track undergoes a series of transformations at New York’s Record Plant, Hendrix overdubbing layer upon layer of guitars through the summer. Dylan later claims to have felt so “overwhelmed” by the finished product that he all but regards it as Hendrix’s song. It takes the low-key original — as bleak and sparse as anything on John Wesley Harding — and turns it into something both kaleidoscopic and apocalyptic.

The troubling quality of Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower” perhaps reflected the fact that he, like Dylan, was in a deeply unhappy relationship with his supposed protector. If Hendrix was the joker here, the thief was manager Mike Jeffery, then wresting control away from the guitarist’s original mentor-producer Chas Chandler.

Jeffery was part Get Carter gangster, part Age-of-Aquarius bullshitter. Born in south London, he told tales of working for MI5 and resembled a low-ranking Long Island mafioso. He wore double-breasted suits with fat paisley ties, his eyes masked by Aviator shades and his lank black hair falling over his shirt collar. There is no evidence that he worked for MI5, but he certainly worked in espionage before muscling in on the nightclub scene in northeast England. He may even have played a part in getting the notorious François “Papa Doc” Duvalier elected to the presidency of Haiti in 1957. And working with him there was the equally shady Jerry Morrison, a former song plugger (born Gerald Herbert Breitman) who’d worked for Louis Armstrong and other jazz stars — and for Papa Doc.

Jeffery and Morrison renewed their acquaintance in New York in 1968, by which time Jeffery — in emulation of Albert Grossman — had bought a large Woodstock home on the southeast corner of Lower Byrdcliffe Road. Hendrix began making visits to 1 Wiley Lane that year and was given the use of a small apartment over its garage. (Like Van Morrison, he was all too aware that his idol Bob Dylan lived barely a quarter mile away.) Perhaps he even believed that Jeffery was sincere in his stated desire to enter into the spirit of the place. There were parties at the house, their host sometimes dropping LSD with his guests. “Mike was taking a bunch of acid with Jimi,” Hendrix’s studio manager Jim Marron claimed. “He was getting very spiritual.”

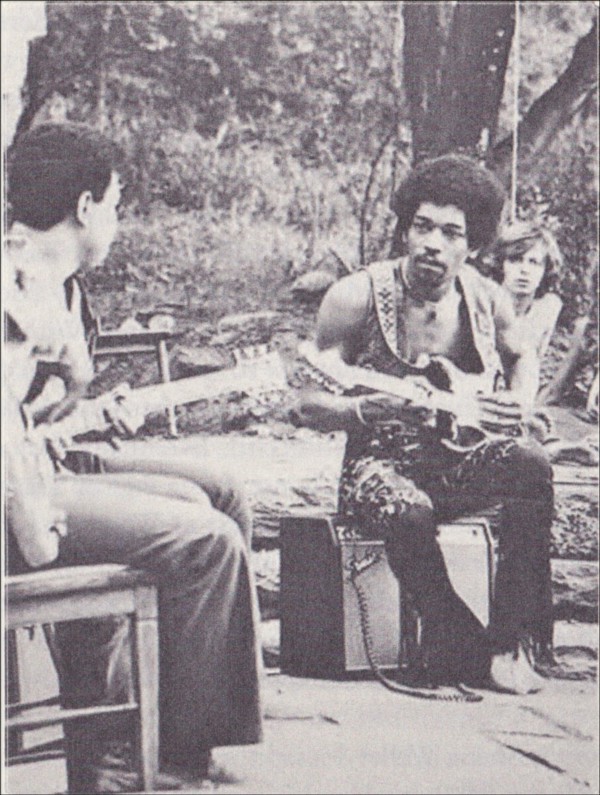

Hendrix was staying in the Wiley Lane apartment when he drove down Rock City Road one afternoon and heard an old New York acquaintance jamming on the village green. Juma Sultan had been commuting between Woodstock and the city since 1966, when he became involved with the Saugerties-based arts collective Group 212. He and percussionist Ali Abuwi had formed a loose Afrocentric entity known as the Aboriginal Music Society, playing around Woodstock and bringing together jazz and R&B musicians united by a commitment to black consciousness.

“Their scene was 24/7, and they had connections in New York with great players who came up,” says drummer Daoud Shaw. “But I never saw a real master plan.” When Sultan told Hendrix what he was up to, the guitarist invited him back to Wiley Lane for a jam. “He was telling me about how he wanted to start a new band,” Sultan remembered. “He was thinking about getting a house in the area, and that’s when his quest for a house started, looking for a place that could become a band house up in Woodstock.”

Though Hendrix kept a low profile in town — since it was rather harder for him to blend in than it was for, say, Rick Danko — he was occasionally seen bombing along Tinker Street in a red Corvette. “Nobody in Woodstock had a red Corvette,” remembered Leslie Aday, who worked for Albert Grossman and befriended Hendrix that summer. “They were all into organic vegetables and making their own clothes.” On at least one occasion, Hendrix went to the Elephant to see a gig.

“The vibe was that he wanted to hang and connect the dots and not be Jimi Hendrix,” says musician Jon Gershen, who observed him at the club. “He was really hungry to understand how Dylan had undergone his transformation. He was feeling the Woodstock thing and wanting to make it work for him, even though it was too much of a stretch to go from where he had been to being, you know, a farmer.”

Two months after Hendrix returned from his last European tour with the Experience — and with a heroin bust from Toronto hanging ominously over him — Mike Jeffery asked Jerry Morrison to find the guitarist a house in the Woodstock area. With Juma Sultan in tow, Morrison took Hendrix to see at least four properties around Woodstock, including a large place that Johnny Winter had rented across the Hudson in Rhinecliff. Eventually they settled on an eight-bedroom stone manor house at the end of Traver Hollow Road in Boiceville, four miles southwest of Woodstock. For a city boy it was quite the retreat, complete with horses in stables and a gatehouse where Sultan and his Chinese-American girlfriend would soon install themselves. A half hour’s drive away was the beautiful Peekamoose Road Waterfall, where Hendrix and his guests took acid trips.

When writer Sheila Weller visited the Traver Hollow house, she wrote that all the talk with Hendrix was about “puppies, daybreak, other innocentia,” and that she’d climbed down some rocks to an “icy brook” with the guitarist. He told her he wanted to “write songs about tranquility, about beautiful things.” He put John Wesley Harding on the turntable and played along to “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest,” “riding the rest of the song home with a near-religious intensity.” At the same time, he was leaning toward the kind of avant-garde Afro-jazz-rock espoused by Sultan, who dressed in robes and pushed his friend to explore the fusion of jazz with tribal percussion.

When writer Sheila Weller visited the Traver Hollow house, she wrote that all the talk with Hendrix was about “puppies, daybreak, other innocentia,” and that she’d climbed down some rocks to an “icy brook” with the guitarist. He told her he wanted to “write songs about tranquility, about beautiful things.” He put John Wesley Harding on the turntable and played along to “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest,” “riding the rest of the song home with a near-religious intensity.” At the same time, he was leaning toward the kind of avant-garde Afro-jazz-rock espoused by Sultan, who dressed in robes and pushed his friend to explore the fusion of jazz with tribal percussion.

If Hendrix was undergoing an identity crisis — did he want to be Bob Dylan or did he want to be Miles Davis? — he was keen to jettison the Experience, complaining to Sheila Weller that he didn’t want to be a “clown” anymore. The sprawlingly eclectic double album Electric Ladyland of 1968 had made his ambitions clear, though the sessions had so frustrated Chas Chandler that he quit and left Hendrix to the mercy of Mike Jeffery.

Jeffery himself was perturbed by any threat to the cash cow that was the Experience, which played its last show on June 1. Used to regular income from the group’s festival appearances, Jeffery watched with unease as a motley crew of musicians rolled up at the Traver Hollow house.

“Because he had the resources,” says singer Martha Velez, “he just brought everybody up to woodshed in that house and ride horses and try that Woodstock meditative approach to writing and creating. He was a very intelligent person who was getting trapped in his own creation. It was important to break out of that, but on his own terms. And to do that he had to have a space where there wasn’t a lot of observation.”

Having coined the name Electric Sky Church for the new ensemble — a reference to the fact that the house sat high above the Ashokan Reservoir — Hendrix now changed the name to Gypsy, Sun and Rainbows. The name was suitably cosmic-bucolic but masked a lack of cohesion, as working titles such as “Jam Back at the House” and “Woodstock Improvisation” make clear. Hendrix may have abandoned the tight pop structures of the Experience, but he was floundering in his new role as improvisatory ringmaster. During one jam session in the house he became so frustrated that he hurled his guitar across the room.

He was also becoming ever more unhappy with his dependency on Mike Jeffery. With no control over his own finances, he constantly had to ask his manager for cash. “If Jimi wanted to buy a car, he had to go to them,” Juma Sultan remembered. “And they always claimed he was broke. He was maintaining this whole cadre of people and he knew it, but there was no way he could go against it.” To make matters worse, Jeffery was siphoning Hendrix’s money off into a bank account in the Bahamas. The guitarist’s sometime girlfriend Monika Dannemann maintained that he had even set up the heroin bust in Toronto “as a warning to teach Jimi a lesson.

In July, Jeffery was approached by Michael Lang with an offer for Hendrix to headline the final day of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair. Supposedly he got the offer upped to $32,000 for two sets, more than twice as much as any other act was getting. With serious misgivings, Hendrix agreed to play and began rehearsing the band in earnest. “I was sitting with him,” says Martha Velez, who’d just returned from recording her Joplin-esque album Fiends and Angels in London, “and he said to me, ‘We’re going to be playing at this festival at White Lake in August. Would you like to come up and sing?’ I said, ‘Oh no, that’s okay.’ What was I thinking? But it was just too much for me.”

On Sunday, August 10 — three days after returning from a week’s holiday in Morocco — Hendrix headed into Woodstock for a jam session at the Tinker Street Cinema, a former Methodist Church converted into a movie house by Woodstock Motel owner Bill Militello. “I remember the music coming out of there,” says Richard Heppner, a boy at the time. “My dad got so pissed about the noise. It was only later that I realized it was Hendrix.”

According to Alan Gordon, the jam took place the same night Johnny Winter played the Café Espresso and Van Morrison sat in at the Sled Hill Café. Also in town for a show at the Elephant were rising Latin-rock stars Santana, whose percussionists Michael Carabello and Jose “Pepe” Areas joined Hendrix, Sultan, and fellow Aboriginal Society members Ali Abuwi and trumpeter Earl Cross for long workouts entitled “The Dance” and “JL (Earth Blues).”

The final number the sextet played that night was a spaced-out arrangement of a famous song that Hendrix had already played several times with the Experience — and which he was considering for his set at the Woodstock Music and Art Fair. “It was less than a week before the festival, and Jimi was practicing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at the Tinker Street Cinema,” Alan Gordon later reflected. “I said, ‘God, look at this amazing place we’re living in here!’”

Excerpted from Small Town Talk: Bob Dylan, The Band, Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Friends in the Wild Years of Woodstock by Barney Hoskyns. Available now from Da Capo Press via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other fine retailers.

Excerpted from Small Town Talk: Bob Dylan, The Band, Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Friends in the Wild Years of Woodstock by Barney Hoskyns. Available now from Da Capo Press via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other fine retailers.